Culture Name

Ghanaian

Alternative Name

Formally known as the Republic of Ghana

Orientation

Identification. Ghana, formerly the British colony of the Gold Coast, assumes a special prominence as the first African country to acquire independence from European rule. Ghanaian politicians marked this important transition by replacing the territory’s colonial label with the name of a great indigenous civilization of the past. While somewhat mythical, these evocations of noble origins, in combination with a rich cultural heritage and a militant nationalist movement, have provided this ethnically diverse country with unifying symbols and a sense of common identity and destiny. Over forty years of political and economic setbacks since independence have tempered national pride and optimism. Yet, the Ghanaian people have maintained a society free from serious internal conflict and continue to develop their considerable natural, human, and cultural resources.

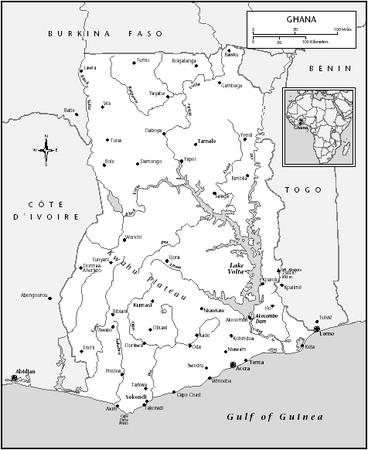

Location and Geography. Ghana is located on the west coast of Africa, approximately midway between Senegal and Cameroon. It is bordered by Côte d’Ivoire (Ivory Coast), Burkina Faso, Togo, and the Atlantic Ocean. The land surface of 92,100 square miles (238,540 square kilometers) is dominated by the ancient Precambrian shield, which is rich in mineral resources, such as gold and diamonds. The land rises gradually to the north and does not reach an altitude of more than 3,000 feet (915 meters). The Volta River and its basin forms the major drainage feature; it originates in the north along two widely dispersed branches and flows into the sea in the eastern part of the country near the Togolese border. The Volta has been dammed at Akosombo, in the south, as part of a major hydroelectric project, to form the Lake Volta. Several smaller rivers, including the Pra and the Tano, drain the regions to the west. Highland areas occur as river escarpments, the most extensive of which are the Akwapim-Togo ranges in the east, the Kwahu escarpment in the Ashanti region, and the Gambaga escarpment in the north.

Ghana’s subequatorial climate is warm and humid, with distinct alternations between rainy summer and dry winters. The duration and amount of rainfall decreases toward the north, resulting in a broad differentiation between two regions— southern rain forest and northern savanna—which form distinct environmental, economic, and cultural zones. The southern forest is interrupted by a low-rainfall coastal savanna that extends from Accra eastward into Togo.

Demography. The population in 2000 was approximately 20 million and was growing at a rate of 3 percent per year. Approximately two-thirds of the people live in the rural regions and are involved in agriculture. Settlement is concentrated within the “golden triangle,” defined by the major southern cities of Accra (the capital), Kumasi, and Sekondi-Takoradi. Additional concentrations occur in the northernmost districts, especially in the northeast. The population is almost exclusively African, as Ghana has no history of intensive European settlement. There is a small Lebanese community, whose members settled in the country as traders. Immigration from other African countries, notably Burkina Faso, Togo, Liberia, and Nigeria, is significant. Some of the better established immigrant groups include many Ghanaian-born members, who are nevertheless classified as “foreign” according to Ghana’s citizenship laws.

Linguistic Affiliation. Ghana’s national language is English, a heritage of its former colonial status. It is the main language of government and instruction.

Ghanaians speak a distinctive West African version of English as a standard form, involving such usages as chop (eat) and dash (gift). English is invariably a second language. Mother tongues include over sixty indigenous languages. Akan is the most widely spoken and has acquired informal national language status. In addition to the large number of native speakers, many members of other groups learn Akan as a second language and use it fluently for intergroup communication. Ga-Adangme and Ewe are the next major languages. Hausa, a Nigerian language, is spoken as a trade language among peoples from the north. Many Ghanaians are multilingual, speaking one or two indigenous languages beside their native dialects and English. Although Ghana is bounded by francophone nations on all sides, few Ghanaians are proficient in French.Symbolism. As a relatively new nation, Ghana has not developed an extensive tradition of collective symbols. Its most distinctive emblems originated in the nationalist movement. The most prominent is the black star, which evokes black pride and power and a commitment to pan-African unity, which were central themes for mobilizing resistance against British rule. It is featured on the flag and the national coat of arms, and in the national anthem. It is also the name of Ghana’s soccer team and is proudly displayed in Black Star Square, a central meeting point in the capital. Other important symbols derive from Akan traditions that have become incorporated into the national culture. These include the ceremonial sword, the linguist’s staff, the chief’s stool, and the talking drum. Ghanaian national dress, kente cloth, is another source of common identity and pride. It is handwoven into intricate patterns from brilliantly colored silk. Men drape it around their bodies and women wear it as a two-pieced outfit. The main exports—gold and cocoa—also stand as identifying symbols.

History and Ethnic Relations

Emergence of the Nation. Ghana is a colonial creation, pieced together from numerous indigenous societies arbitrarily consolidated, and sometimes divided, according to European interests. There is no written documentation of the region’s past prior to European contact. By the time the Portuguese first established themselves on the coast in the fifteenth century, kingdoms had developed among various Akan-speaking and neighboring groups and were expanding their wealth, size, and power. The Portuguese quickly opened a sea route for the gold trade, and the emergence of the “Gold Coast” quickly attracted competition from Holland, England, France, and other European countries. With the development of American plantation systems, slaves were added to the list of exports and the volume of trade expanded. The Ashanti kingdom emerged as the preeminent Akan political force and established its rule over several neighboring groups and into the northern savanna. Some indigenous states on the margins of Ashanti expansion, such as Akim and Akwapem, retained their independence. Coastal peoples were able to resist conquest through alliances with European powers.

In the nineteenth century, England assumed dominance on the coast and developed a protectorate over the local African communities. England came into conflict with Ashanti over coastal expansion and the continuation of the slave trade. At the end of the nineteenth century, it defeated Ashanti and established the colony of the Gold Coast, including the coastal regions, Ashanti, and the Northern Territories beyond. The boundaries of this consolidation, which included many previously separate and independent kingdoms and tribal communities, were negotiated by the European powers to suit their strategic and economic interests. After 1918, England further complicated this arrangement by annexing the trans-Volta region from German Togoland as a spoil of World War I.

The colony was administered under the system of indirect rule, in which the British controlled affairs at the national level but organized local control through indigenous rulers under the supervision of colonial district commissioners. Western investment, infrastructure, and institutional development were concentrated in the urban complexes that emerged within the coastal ports. Educational and employment opportunities were created for Africans, mostly from coastal communities, but only for the purpose of staffing the lower echelons of the public and commercial sectors. The rural masses were disadvantaged by the colonial regime and the exactions of their chiefs but gained some degree of wealth and local development through the growth of a lucrative export trade in cocoa, especially in the forest zone. The north received little attention.

Resistance to British rule and calls for independence were initiated from the onset of colonial rule. Indigenous rulers formed the initial core of opposition, but were soon co-opted. The educated Westernized coastal elite soon took up the cause, and the independence movement remained under their control until the end of World War II. After the war, nationalists formed the United Gold Coast Convention and tried to broaden their base and take advantage of mass unrest that was fed by demobilization, unemployment, and poor commodity prices. They brought in Kwame Nkrumah, a former student activist, to lead this campaign. Nkrumah soon broke ranks with his associates and formed a more radical movement though the Convention People’s Party. He gained mass support from all parts of the colony and initiated strikes and public demonstrations that landed him in jail but finally forced the British to grant independence. The Gold Coast achieved home rule in 1951. On 6 March 1957 it became the self-governing country of Ghana, the first sub-Saharan colony to gain independence. In the succeeding decades, Ghana experienced a lot of political instability, with a series of coups and an alternation between civilian and military regimes.

National Identity. In spite of its disparate origins and arbitrary boundaries, Ghana has developed a modest degree of national coherence. British rule in itself provided a number of unifying influences, such as the use of English as a national language and a core of political, economic, and service institutions. Since independence, Ghanaian leaders have strengthened national integration, especially through the expansion of the educational system and the reduction of regional inequalities. They have also introduced new goals and values through the rhetoric of the independence movement, opposition to “neo-colonialist” forces, and advocacy of pan-Africanism. A second set of common traditions stem from indigenous cultures, especially from the diffusion of Akan institutions and symbols to neighboring groups.

Ethnic Relations. Ghana contains great diversity of ethnic groups. The Akan are the most numerous, consisting of over 40 percent of the population. They are followed by the Ewe, Ga, Adangme, Guan, and Kyerepong in the south. The largest northern groups are the Gonja, Dagomba, and Mamprussi, but the region contains many small decentralized communities, such as the Talensi, Konkomba, and Lowiili. In addition, significant numbers of Mossi from Burkina Faso have immigrated as agricultural and municipal workers. Nigerian Hausa are widely present as traders.

Intergroup relations are usually affable and Ghana has avoided major ethnic hostilities and pressure for regional secession. A small Ewe separatist movement is present and some localized ethnic skirmishes have occurred among small communities in the north, mostly over boundary issues. There is, however, a major cultural divide between north and south. The north is poorer and has received less educational and infrastructural investment. Migrants from the region, and from adjoining areas of Burkina Faso, Togo, and Nigeria typically take on menial employment or are involved in trading roles in the south, where they occupy segregated residential wards called zongos. Various forms of discrimination are apparent.

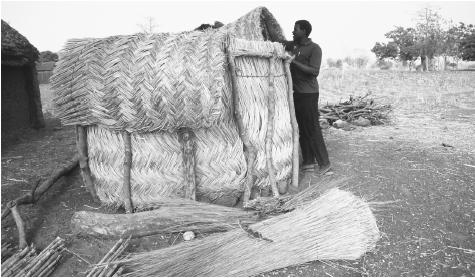

Urbanism, Architecture, and the Use of Space

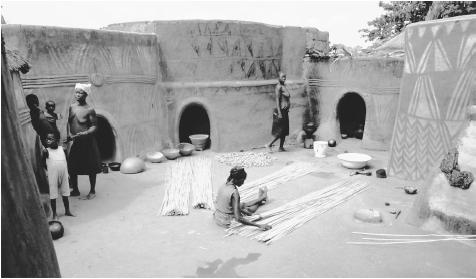

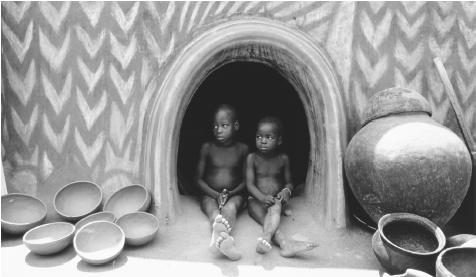

Although Ghana is primarily a rural country, urbanization has a long tradition within indigenous and modern society. In the south the traditional settlement was a nucleated townsite that served as a king’s or a chief’s administrative base and housed the agricultural population, political elite, and occupational specialists. In precolonial times, populations in these centers ranged from a few hundred to several thousand in a major royal capital, such as Kumasi, which is now Ghana’s second largest city. Traditional political nodes also served economic functions concentrated in open-air marketplaces, which still constitute a central feature of traditional and modern towns. Housing consists of a one-story group of connected rooms arranged in a square around a central courtyard, which serves as the primary focus of domestic activity. The chief’s or king’s palace is an enlarged version of the basic household. Settlement in the north follows a very different pattern of dispersed farmsteads.

The British administration introduced Western urban infrastructures, mainly in the coastal ports, such as Accra, Takoradi, and Cape Coast, a pattern that postcolonial governments have followed. Thus central districts are dominated by European-style buildings, modified for tropical conditions. Neither regime devoted much attention to urban planning or beautification, and city parks or other public spaces are rare. Accra contains two notable monuments: Black Star Square and the Kwame Nkrumah Mausoleum, symbols of Ghana’s commitment to independence and African unity.

Much of the vibrancy of urban life is due to the incorporation of indigenous institutions, especially within the commercial sector. Commerce is dominated by open-air markets, such as the huge Markola market in Accra, where thousands of traders offer local and imported goods for sale. Although the very wealthy have adopted Western housing styles, most urban Ghanaians live in traditional dwellings, in which renters from a variety of backgrounds mingle in central courtyards in much

the same way that family members do in traditional households. Accordingly, marketplaces and housing compounds provide the predominant settings for public interaction.

Food and Economy

Food in Daily Life. The basic diet consists of a starchy staple eaten with a soup or stew. Forest crops, such as plantain, cassava, cocoyam (taro), and tropical yams, predominate in the south. Corn is significant, especially among the Ga, and rice is also popular. The main dish is fufu, pounded plantain or tubers in combination with cassava. Soup ingredients include common vegetables and some animal protein, usually fish, and invariably, hot peppers. Palm nut and peanut soups are special favorites. The main cooking oil is locally produced red palm oil. The northern staple is millet, which is processed into a paste and eaten with a soup as well. Indigenous diets are eaten at all social levels, even by the Westernized elite. Bread is the only major European introduction and is often eaten at breakfast. Restaurants are not common outside of urban business districts, but most local “chop bars” offer a range of indigenous dishes to workers and bachelors. People frequently snack on goods offered for sale by street hawkers.

Food Customs at Ceremonial Occasions. Most households raise chickens and dwarf goats, which are reserved for special occasions, such as christenings, weddings, traditional festivals, and Christmas. Among the Akan, the main indigenous celebration is odwira, a harvest rite, in which new yams are presented to the chief and eaten in public and domestic feasts. The Ga celebrate homowo, another harvest festival, which is marked by eating kpekpele, made from mashed corn and palm oil. Popular drinks include palm wine, made from the fermented sap of the oil palm, and home-brewed millet beer. Bottled European-style beer is widely consumed. Imported schnapps and whiskey have important ceremonial uses as libations for royal and family ancestors.

Basic Economy. Ghana’s position in the international economy reflects a heavy dependence on primary product exports, especially cocoa, gold, and timber. International trade accounts for one-third of gross domestic product (GDP), and 70 percent of export income is still derived from the three major commodities. The domestic economy is primarily agricultural with a substantial service and trading sector. Industrial production comprises only 10 percent of national output, and consumers are heavily dependent upon imported manufactures as well as petroleum imports.

Land Tenure and Property. Traditional land use patterns were organized around a slash-and-burn system in which crops were grown for two or three years and then fallowed for much longer periods. This system fostered communal land tenure systems, in which a large group, usually the lineage, held the land in trust for its members and allocated usufruct rights on demand. In the south, reserved lands, known as stool lands, were held by the chief for the wider community. The stool also held residual rights in lineage-owned land, for instance a claim on any gold found. In the north, communal rights were invested in a ritual figure, the tendana, who assumed the ultimate responsibility for agriculture rituals and land allocation.

In modern times, land tenure has been widely affected by cocoa farming and other commercial uses, which involve a permanent use of the land and a substantial expansion in demand for new plots. Land sales and long-term leases have developed in some areas, often on stool reserves. Purchased lands are considered private rather than family or communal property and activate a different inheritance pattern, since they can be donated or willed without reference to the standard inheritance rule.

Government regulation of land title has normally deferred to traditional arrangements. Currently, a formally constituted Lands Commission manages government-owned lands and gold and timber reserve leases and theoretically has the right to approve all land transfers. Nevertheless, most transactions are still handled informally according to traditional practice.

Commercial Activities. While strongly export oriented, Ghanaian farmers also produce local foods for home consumption and for a marketing system that has developed around the main urban centers. Rural household activities also include some food processing, including palm oil production. The fishery is quite important. A modern trawler fleet organizes the offshore catch and supplies both the domestic and overseas markets. Small-scale indigenous canoe crews dominate the inshore harvest and supply the local markets. Traditional crafts have also had a long tradition of importance for items such as pottery, handwoven cloth, carved stools, raffia baskets, and gold jewelry. There are also many tailors and cabinetmakers.

Major Industries. Manufactured goods are dominated by foreign imports, but some local industries have developed, including palm oil milling, aluminum smelting, beer and soft drink bottling, and furniture manufacturing. The service sector is dominated by the government on the high end and the small-scale sector, sometimes referred to as the “informal sector,” on the low end. Education and health care are the most important public services. Transport is organized by small-scale owner-operators. Construction is handled by the public, private, or small-scale sector depending upon the nature of the project.

Trade. Cocoa is grown by relatively small-scale indigenous farmers in the forest zone and is exclusively a commercial crop. It is locally marketed through private licensed traders and exported through a public marketing board. Gold is produced by international conglomerates with some Ghanaian partnership. Much of the income from this trade is invested outside the country. Timber is also a large-scale formal-sector enterprise, but there is a trend toward developing a furniture export industry among indigenous artisans. Other exports include fish, palm oil, rubber, manganese, aluminum, and fruits and vegetables. Internal trade and marketing is dominated by small-scale operations and provides a major source of employment, especially for women.

Division of Labor. Formal sector jobs, especially within the public service, are strictly allocated on the basis of educational attainment and paper qualifications. Nevertheless, some ethnic divisions are noticeable. Northerners, especially Mossi, and Togolese hold the more menial positions. Hausa are associated with trade. Kwahu are also heavily engaged in trade and also are the main shopkeepers. Ga and Fante form the main fishing communities, even along the lakes and rivers removed from their coastal homelands. Age divisions are of some importance in the rural economy. Extended family heads can expect their junior brothers, sons, and nephews to assume the major burdens of manual labor.

Social Stratification

Classes and Castes. Ghana’s stratification system follows both precolonial and modern patterns. Most traditional kingdoms were divided into three hereditary classes: royals, commoners, and slaves. The royals maintained exclusive rights to fill the central offices of king and, for Akan groups, queen mother. Incumbents acquired political and economic privileges, based on state control over foreign trade. Unlike European nobilities, however, special status was given only to office-holders and not their extended families, and no special monopoly over land

was present. Moreover, royals regularly married commoners, a consequence of a rule of lineage out-marriage. Freemen held a wide variety of rights, including unhampered control over farm land and control over subordinate political positions. Slavery occurred mainly as domestic bondage, in which a slave could command some rights, including the ability to marry a nonslave and acquire property. Slaves were also used by the state for menial work such as porterage and mining.Slavery is no longer significant. Traditional royalties are still recognized but have been superseded by Westernized elites. Contemporary stratification is based on education and, to a lesser degree, wealth, both of which have led to significant social mobility since independence. Marked wealth differences have also emerged, but have been moderated by extended family support obligations and the communal rights that most Ghanaians hold in land. Northerners, however, form a noticeable underclass, occupying low status jobs. Bukinabe and Togolese are especially disadvantaged because, as foreigners, they cannot acquire land.

Symbols of Social Stratification. In traditional practice, kings and other hereditary officials marked their status through the use of regalia, such as umbrellas and staves, and the exclusive right to wear expensive clothing, such as kente cloth, and to consume and distribute special imported goods. In modern times, expenditure on Western consumer items has become the dominant status marker. Clothing, both expensive Western and traditional items, is an important symbol of education and wealth. Luxury cars are also significant—a Mercedes-Benz is the most dominant marker of high rank. Status must also be demonstrated in public display, especially in lavish funerals that acclaim both the deceased and their descendants.

Political Life

Government. Although Ghana’s national government was originally founded on a British parliamentary model, the current constitution follows an American tricameral system. The country is a multiparty democracy organized under an elected president, a legislature, and an independent judiciary. It is divided into ten administrative regions, exclusively staffed from the central government. Regions are further subdivided into local districts, organized under district assemblies. The majority of assembly members are elected, but some seats are allocated to traditional hereditary rulers. Chiefs also assume the major responsibility for traditional affairs, including stool land transfers, and are significant actors in local political rituals. They are also represented in the National House of Chiefs, which formulates general policies on traditional issues.

Leadership and Political Officials. Indigenous leaders assume hereditary positions but still must cultivate family and popular support, since several candidates within a descent line normally compete for leadership positions. Chiefs can also be deposed. On the national level, Ghana has been under military rule for a good part of its history, and army leadership has been determined by both rank and internal politics. Civilian leaders have drawn support from a variety of fronts. The first president, Nkrumah, developed a dramatic charisma and gave voice to many unrepresented groups in colonial society. K. A. Busia, who followed him after a military interregnum, represented the old guard and also appealed to Ashanti nationalism. Hillal Limann, the third president, identified himself as an Nkrumahist, acquiring power mainly through the application of his professional diplomatic skills. Jerry Rawlings, who led Ghana for 19 years, acquired power initially through the military and was able to capitalize on his position to prevail in civil elections in 1992 and 1996. He stepped down in 2000, and his party was defeated by the opposition, led by John Kufuor.

Ghana has seven political parties. Rawlings National Democratic Party is philosophically leftist and advocates strong central government, nationalism and pan-Africanism. However, during the major portion of its rule it followed a cautious economic approach and initiated a World Bank structural adjustment, liberalization, and privatization program. The current ruling party (as of 2001) is the New Patriotic Party. It has assumed the mantle of the Busia regime and intends to pursue a more conservative political and economic agenda than the previous regime.

Secular politicians are dependent upon the electorate and are easily approachable without elaborate ceremony. Administrators in the public service, however, can be quite aloof. Traditional Akan chiefs and kings are formally invested with quasi-religious status. Their subjects must greet them by prostrating themselves and may talk to them only indirectly through the chief’s “linguist.”

Social Problems and Control. The Ghanaian legal system is a mixture of British law, applicable to criminal cases, and indigenous custom for civil cases. The formal system is organized under an independent judiciary headed by a supreme court. Its independence, however, has sometimes been compromised by political interference, and, during Rawling’s military rule, by the establishment of separate public tribunals for special cases involving political figures. These excesses have since been moderated, although the tribunal system remains in place under the control of the Chief Justice. Civil cases that concern customary matters, such as land, inheritance, and marriage, are usually heard by a traditional chief. Both criminal and civil laws are enforced by a national police force.

People are generally wary of the judicial system, which can involve substantial costs and unpredictable outcomes. They usually attempt to handle infractions and resolve disputes informally through personal appeal and mediation. Strong extended family ties tend to exercise a restraint on deviant behavior, and family meetings are often called to settle problems before they become public. Marital disputes are normally resolved by having the couple meet with the wife’s uncle or father, who will take on the role of a marriage counselor and reunite the parties.

Partially because of the effective informal controls, the level of violent crime is low. Theft is the most common infraction. Smuggling is also rampant, but is not often prosecuted since smugglers regularly bribe police or customs agents.

Military Activity. Ghana’s military, composed of about eight thousand members, includes an army and a subordinate navy and air force. There is also the People’s Militia, responsible for controlling civil disturbances, and a presidential guard. Government support for these services is maintained at approximately 1 percent of GDP. The army leadership has demonstrated a consistent history of coups and formed the national government for approximately half of the time that the country has been independent. Ghana has not been involved in any wars since World War II and has not suffered any civil violence except for a few localized ethnic and sectarian skirmishes. It has participated in peacekeeping operations, though the United Nations, the Organization of African Unity, and the West African Community. The most recent interventions have been in Liberia and Sierra Leone.

Social Welfare and Change Programs

Ghana is a low income country with a per capita GDP of only $400 (U.S.) per year. It has many economic and social problems especially in the areas of employment, housing, health, and sanitation.

The major thrust of development policy since 1985 has the World Bank–supported Economic Recovery Program, a structural adjustment strategy to liberalize macroeconomic policy. The core initiatives have been expansion and diversification of export production, reduction of government expenditures, especially in the public service, and privatization of state industries. As part of this program, the government instituted a special project to address the attendant social costs of these policies. It involved attempts to increase employment through public works and private-sector expansion, supported by business loans to small-scale entrepreneurs and laid-off public servants. Women were particularly targeted as beneficiaries.

Nongovernmental Organizations and Other Associations

Ghana has an active Nongovernmental Organization (NGO) sector, with over 900 registered organizations that participate in welfare and development projects in health, education, microfinancing, women’s status, family planning, child care, and numerous other areas. The longest standing groups have been church-based organizations and the Red Cross. Most are supported by foreign donors. Urban voluntary associations, such as ethnic and occupational unions, also offer important social and economic assistance.

Gender Roles and Statuses

Division of Labor by Gender. Gender division varies across different ethnic groups. Among the Akan, women assume the basic domestic and childcare roles. Both genders assume responsibility for basic agriculture production, although men undertake the more laborious tasks and women the more repetitive ones. Women will work on their husbands’ farms but will also farm on their own. Traditional craft production is divided according to gender. Men are weavers, carvers, and metalworkers. Women make pottery and engage in food processing. Petty trade, which is a pervasive economic activity, is almost exclusively a woman’s occupation. Women independently control any money that they receive from their own endeavors, even though their husbands normally provide the capital funding. Wives, however, assume the main work and financial responsibility for feeding their husbands and children and for other child-care expenses.

Akan women also assume important social, political, and ritual roles. Within the lineage and extended family, female elders assume authority, predominantly over other women. The oldest women are considered to be the ablest advisers and the repositories of family histories.

Among the Ga and Adangme, women are similarly responsible for domestic chores. They do not do any farmwork, however, and are heavily engaged in petty trade. Ga women are especially prominent traders as they control a major portion of the domestic fish industry and the general wholesale trade for Accra, a Ga homeland. Northern and Ewe women, on the other hand, have fewer commercial opportunities and assume heavier agricultural responsibilities in addition to their housekeeping chores.

The Relative Status of Women and Men. In traditional society, women had considerable economic and political powers which derived in part from their ability to control their own income and property without male oversight. Among the matrilineal Akan they also regularly assumed high statuses within the lineage and the kingdom, even though their authority was often confined to women’s affairs. Colonialism and modernization has changed women’s position in complex ways. Women have retained and expanded their trading opportunities and can sometimes acquire great wealth through their businesses. Men have received wider educational opportunities, however, and are better represented in government and formal sector employment. A modest women’s movement has developed to address gender differences and advance women’s causes.

Marriage, Family, and Kinship

Marriage. Tradition dictates that family elders arrange the marriages of their dependents. People are not allow to marry within their lineages, or for the Akan, their wider clan groups. There is a preference, however, for marriage between cross-cousins (children of a brother and sister). The groom’s family is expected to pay a bride-price. Polygyny is allowed and attests to the wealth and power of men who can support more than one wife. Chiefs mark their status by marrying dozens of women. Having children is the most important focus of marriage and a husband will normally divorce an infertile wife. Divorce is easily obtained and widespread, as is remarriage. Upon a husband’s death, his wife is expected to marry his brother, who also assumes responsibility for any children.

The spread of Western values and a cash economy have modified customary marriage patterns. Christians are expected to have only one wife. Monogamy is further supported by the ability of men to marry earlier than they could in traditional society because of employment and income opportunities in the modern sector. Young men and women have also been granted greater latitude to choose whom they marry. Accordingly, the incidence of both polygyny and cousin marriage is low. There is, however, a preference for marriages within ethnic groups, especially between people from the same town of origin.

Domestic Unit. The basic household group is formed on a complex set of traditional and contemporary forces. Akan custom allows for a variety of forms. The standard seems to have been natalocal, a system in which each spouse remained with his or her family of origin after marriage. Children would remain with their mothers and residential units would consist of generations of brothers, sisters, and sisters’ children. Wives, however, would be linked to their husbands economically. Men were supposed to provide support funds and women were supposed to cook for their husbands. Alternative forms were also present including avunculocal residence, in which a man would reside with his mother’s brother upon adulthood, and patrilocality, in which children would simply remain with their fathers upon adulthood. In all of these arrangements men would assume the basic role of household head, but women had some power especially if they were elderly and had many younger women under their authority.

The Akan domestic arrangements are based on matrilineal principles. All other Ghanaian ethnic groups are patrilineal and tend toward patrilocal residence. The Ga, however, have developed an interesting pattern of gender separation. Men within a lineage would live in one structure, and their wives and unmarried female relatives would live in a nearby one. In the north, patrilocal forms were complicated by a high incidence of polygynous marriage. A man would assign a separate hut to each of his wives, and, after their sons married, to each of their wives. The man would act has household head but delegate much of the domestic management to his wives, especially senior wives with several daughters-in-law.

Modern forces have influenced changes in domestic forms. Western values, wage employment, and geographical mobility have led to smaller and more flexible households. Nuclear families are now more numerous. Extended family units are still the rule, but they tend to include relatives on an ad hoc basis rather than according to a fixed residence rule.

Sibling bonds are strong, and household heads will often include younger brothers and sisters and nieces and nephews from either side of the family within their domestic units. They may also engage resident domestic help, who are often relatives but may come from other families. Important economic bonds continue to unite extended kin who live in separate physical dwellings but still share responsibilities to assist one another and sometimes engage in joint enterprises.Inheritance. Most Ghanaian inheritance systems share two features: a distinction between family and individual property and a preference for siblings over children as heirs. Among the matrilineal Akan, family property is inherited without subdivision, in the first instance by the oldest surviving brother. When the whole generation of siblings dies out, the estate then goes to the eldest sister’s eldest son. Women can also inherit, but there is a preference for men’s property to pass on to other men and women’s to other women. Private property can be passed on to wives and children of the deceased through an oral or written will. In most cases, it will be divided equally among wives, children, and matrilineal family members. Private property passed on to a child remains private. If it is inherited within the matrilineage, it becomes family property. Among patrilineal groups, sibling inheritance applies as well, but the heir will be expected to support the children of the deceased. If he assumes responsibility for several adult nephews he will invariably share the estate with them.

Kin Groups. Localized, corporate lineage groups are the basic units of settlement, resource ownership, and social control. Among the Akan, towns and villages are comprised of distinct wards in which matrilineal descendants ( abusua ) of the same ancestress reside. Members of this group jointly own a block of farmland in which they hold hereditary tenure rights. They usually also own the rights to fill an office in the settlement’s wider administration. The royal lineage holds title to the chief’s and queen mother’s position. Lineages have an internal authority structure under the male lineage elder ( abusua panyin ), who decides on joint affairs with the assistance of other male and female elders. The lineage is also a ritual unit, holding observances and sacrifices for its important ancestors. Patrilineal groups in Ghana attach similar economic, political, and ritual importance to the lineage system.

Socialization

Infant Care. Young children are treated with affection and indulgence. An infant is constantly with its mother, who carries it on her back wrapped in a shawl throughout the day. At night it sleeps with its parents. Breast-feeding occurs on demand and may continue until the age of two. Toilet training and early discipline are relaxed. Babies receive a good deal of stimulation, especially in social contexts. Siblings, aunts, uncles, and other relatives take a keen interest in the child and often assume caretaking responsibilities, sometimes on an extended basis.

Child Rearing and Education. Older children receive considerably less pampering and occupy the bottom of an age hierarchy. Both boys and girls are expected to be respectful and obedient and, more essentially, to take significant responsibilities for domestic chores, including tending their younger siblings. They are also expected to defer to adults in a variety of situations.

Coming of age is marked within many Ghanaian cultures by puberty ceremonies for girls that must be completed before marriage or childbirth. These are celebrated on an individual rather than a group basis. Boys have no corresponding initiation or puberty rites. Most children attend primary school, but secondary school places are in short supply. The secondary system is based mainly on boarding schools in the British tradition and resulting fees are inhibitive. Most adolescents are engaged in helping on the farm or in the family business in preparation for adult responsibilities. Many enter apprenticeships in small business operations in order to learn a trade. The less fortunate take on menial employment, such as portering, domestic service, or roadside hawking.

Higher Education. Only a tiny percentage of the population has the opportunity to enter a university or similar institution. University students occupy a high status and actively campaign, sometimes through strikes, to maintain their privileges. Graduates can normally expect high-paying jobs, especially in the public sector. Attendance at overseas institutions is considered particularly prestigious.

Etiquette

Ghanaians place great emphasis on politeness, hospitality, and formality. Upon meeting, acquaintances must shake hands and ask about each other’s health and families. Visitors to a house must greet and shake hands with each family member. They are then seated and greeted in turn by all present. Hosts must normally provide their guests with something to eat and drink, even if the visit does not occur at a mealtime. If a person is returning from or undertaking a long journey, a libation to the ancestors is usually poured. If someone is eating, he or she must invite an unexpected visitor to join him or her. Normally, an invitation to eat cannot be refused.

Friends of the same age and gender hold hands while walking. Great respect is attached to age and social status. A younger person addresses a senior as father or mother and must show appropriate deference. It is rude to offer or take an object or wave with the left hand. It is also rude to stare or point at people in public. Such English words as “fool(ish),” “silly,” or “nonsense,” are highly offensive and are used only in extreme anger.

Religion

Religious Beliefs. Christianity, Islam, and traditional African religions claim a roughly equal number of adherents. Christians and Muslims, however, often follow some forms of indigenous practice, especially in areas that do not directly conflict with orthodox belief. Moreover, some Christian sects incorporate African elements, such as drumming, dancing, and possession.

Traditional supernatural belief differs according to ethnic group. Akan religion acknowledges many spiritual beings, including the supreme being, the earth goddess, the higher gods ( abosom ), the ancestors, and a host of spirits and fetishes. The ancestors are perhaps the most significant spiritual force. Each lineage reveres its important deceased members both individually and collectively. They are believed to exist in the afterlife and benefit or punish their descendants, who must pray and sacrifice to them and lead virtuous lives. Ancestral beliefs are also built into political rites, as the ancestors of the royal lineage, especially deceased kings and chiefs, serve as major foci for general public observance.

Religious Practitioners. The abosom are served by priests and priestess ( akomfo ), who become possessed by the god’s spirit. In this state, they are able to divine the causes of illnesses and misfortunes and to recommend sacrifices and treatments to remedy them. They have also played an important role in Akan history. Okomfo Anokye was a priest who brought down the golden stool, the embodiment of the Ashanti nation, from heaven. Lesser priests and priestesses serve the shrines of fetishes, minor spirits, and focus on cures and magic charms. Family elders also assume religious functions in their capacity as organizers of ancestral rites. Chiefs form the focus of rituals for the royal ancestors and assume sacred importance in their own right as quasi-divine beings.

Other ethnic groups also worship through the intercession of priests and chiefs. Ga observances focus on the wulomei, the priests of the ocean, inlets, and lagoons. Their prayers and sacrifices are essential for successful fishing and they serve as advisers to Ga chiefs. In the modern context, the Nai Wulomo, the chief priest, assumes national importance because of his responsibility for traditional ritual in Accra, Ghana’s capital. In the north, the tendana, priests of the earth shrines, have been the

key figures of indigenous religion. They are responsible for making sacrifices for offenses against the earth, including murder, for rituals to maintain land productivity, and for allocating unowned land.Rituals and Holy Places. The most important rituals revolve around the cycle of ancestral and royal observances. The main form is the adae ceremony, in which prayers are made to the ancestors through the medium of carved stools that they owned in their lifetimes. These objects are kept in a family stool house and brought out every six weeks, when libations are poured and animals sacrificed. Royal stools are afforded special attention. The adae sequence culminates in the annual odwira festival, when the first fruits of the harvest are given to the abosom and the royal ancestors in large public ceremonies lasting several days. Royal installations and funerals also assume special ritual importance and are marked by sacrifices, drumming, and dancing.

Death and the Afterlife. Death is one of the most important events in society and is marked by most ethnic groups and religions by elaborate and lengthy funeral observances that involve the whole community. People were traditionally buried beneath the floors of their houses, but this custom is now practiced only by traditional rulers, and most people are interred in cemeteries. After death, the soul joins the ancestors in the afterworld to be revered and fed by descendants within the family. Eventually the soul will be reborn within the same lineage to which it belonged in its past life. People sometimes see a resemblance to a former member in an infant and name it accordingly. They may even apply the relevant kinship term, such as mother or uncle, to the returnee.

Medicine and Health Care

Ghana has a modern medical system funded and administered by the government with some participation by church groups, international agencies, and NGOs. Facilities are scarce and are predominantly located in the cities and large towns. Some dispensaries staffed by nurses or pharmacists have been established in rural areas and have been effective in treating common diseases such as malaria.

Traditional medicine and medical practitioners remain important because of the dearth of public facilities and the tendency for Ghanaians to patronize indigenous and modern systems simultaneously. Customary treatments for disease focus equally on supernatural causes, the psychosociological environment, and medicinal plants. Abosom priests and priestesses deal with illness through prayer, sacrifice, divination, and herbal cures. Keepers of fetish shrines focus more heavily on magical charms and herbs, which are cultivated in a garden adjoining the god’s inclosure. More secularly oriented herbalists focus primarily on medicinal plants that they grow, gather from the forest, or purchase in the marketplace. Some members of this profession specialize in a narrow range of conditions, for example, bonesetters, who make casts and medicines for broken limbs.

Some interconnections between the modern and traditional systems have developed. Western trained doctors generally adopt a preference for injections in response to the local belief that medicines for the most serious diseases must be introduced into the blood. They have also been investigating the possible curative efficacy of indigenous herbs, and several projects for developing new drugs from these sources have been initiated.

Secular Celebrations

Aside from the major Christian and Islamic holidays, Ghana celebrates New Year’s Day, Independence Day (6 March), Worker’s Day (1 May), Republic Day (1 July), and Revolution Day (31 December). New Year’s Day follows the usually western pattern of partying. Independence Day is the main national holiday celebrating freedom from colonial rule and is marked by parades and political speeches. The remaining holidays are also highly politicized and provide forums for speeches by the major national leaders. Revolution Day is especially important for the ruling party as it marks the anniversary of Rawlings’ coup.

The Arts and the Humanities

Support for the Arts. The arts are primarily self supporting, but there are some avenues of government financing and sponsorship. The publically funded University of Ghana, through the Institute for African Studies, provides a training ground for artists, especially in traditional music and dance, and hosts an annual series of public performances. The government also regularly hosts pan-African arts festivals, such as PANAFEST, and sends Ghanaian artists and performers to similar celebrations in other African countries.

Literature. While there is a small body of written literature in indigenous languages, Ghanaians maintain a rich oral tradition, both through glorification of past chiefs and folktales enjoyed by popular audiences. Kwaku Ananse, the spider, is an especially well-known folk character, and his clever and sometimes self-defeating exploits have been sources of delight across generations. Literature in English is well developed and at least three authors, Ayi Kwei Armah, and Efua Sutherland, and Ama Ata Aiddo, have reached international audiences.

Graphic Arts. Ghana is known for a rich tradition of graphic arts. Wood carving is perhaps the most important. The focus of the craft is on the production of stools that are carved whole from large logs to assume the form of abstract designs or animals. These motifs generally represent proverbial sayings. The stools are not merely mundane items, but become the repositories of the souls of their owners after death and objects of family veneration. Carving is also applied to the production of staves of traditional office, drums, dolls, and game boards. Sculpting in metal is also important and bronze and iron casting techniques are used to produce gold weights and ceremonial swords. Ghanaians do not make or use masks, but there are some funerary effigies in clay. Pottery is otherwise devoted to producing simple domestic items. Textiles are well developed, especially handwoven kente, and stamped adinkra cloths.

Most of the traditional crafts involve artists who work according to standardized motifs to produce practical or ceremonial items. Purely aesthetic art is a modern development and there is only a small community of sculptors and painters who follow Western models of artistic production.

Performance Arts. Most performances occur in the context of traditional religious and political rites, which involve intricate drumming and dancing. While these are organized by trained performers, a strong emphasis on audience participation prevails. Modern developments have encouraged the formation of professional troupes, who perform on public occasions, at international festivals, and in theaters and hotel lounges. The University of Ghana houses the Ghana Dance Ensemble, a national institution with an international reputation. More popular modern forms focus on high life music, a samba-like dance style, which is played in most urban nightclubs.

The State of the Physical and Social Sciences

Ghana’s economy is not able to support a robust research and development infrastructure. Scientific developments are modest and focus on the most critical practical concerns. The major research establishment is located in Ghana’s three universities and in government departments and public corporations. Research in the physical sciences is heavily focused on agriculture, particularly cocoa. The Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology in Kumasi concentrates on civil and industrial engineering and medicine. The Ministry of Health also has an active research agenda, which is complemented by World Health Organization activities. Social sciences focus on economic and development issues. The Institute for Statistical, Social, and Economic Research at the University of Ghana has conducted numerous surveys on rural and urban production and income patterns and on household economies and child welfare. The government statistical service carries out demographic and economic research into such areas as income distribution and poverty. Demographic issues are also investigated through the Population Impact Project at the University of Ghana. Education research and development forms another major concern and is the focus for activities at Ghana’s third higher education facility, the University of Cape Coast.

Bibliography

Abu, Katherine. “Separateness of Spouses: Conjugal Resources in an Ashanti Town.” In Christine Oppong, ed., Female and Male in West Africa, 1983.

Apter, David. The Gold Coast in Transition, 1955.

Armstrong, Robert. Ghana Country Assistance Review: A Review of Development Effectiveness, 1996.

Asabere, Paul K. “Public Policy and the Emergent African Land Tenure System.” Journal of Black Studies 24(3): 281–290, 1994.

Berry, LaVerle, ed. Ghana, a Country Study, 3rd ed., 1994.

Busia, K. A. The Position of the Chief in the Modern Political System of the Ashanti: A Study of the Influence of Contemporary Social Change on Ashanti Political Institutions, 1951.

——. “The Ashanti.” In Daryl Forde, ed., African Worlds, 1954.

Essien, Victor. “Sources of Law in Ghana.” Journal of Black Studies 24 (3): 246–263, 1994.

Field, M. J. Religion and Medicine of the Ga People, 1937.

——. Social Organization for the Ga People, 1940.

Fitch, Robert. Ghana: End of an Illusion, 1966.

Fortes, Meyer. The Dynamics of Clanship among the Talensi, 1945.

——. “Kinship and Marriage among the Ashanti.” In A. R. Radcliffe-Brown and D. Forde, eds., African Systems of Kinship and Marriage, 1950.

Goody, Jack. The Social Organisation of the LoWiili, 1956.

——. Changing Social Structure in Ghana, 1975.

Hill, Polly. Migrant Cocoa Farmers of Southern Ghana, 1963.

Jeong, Ho-Won. “Ghana: Lurching toward Economic Rationality.” World Affairs 159 (2): 643–672, 1996.

——. “Economic Reform and Democratic Transition in Ghana.” World Affairs 160 (4): 218–231, 1998.

Kaye, Barrington. Bringing Up Children in Ghana, 1962.

Lentz, Carola, and Paul Nugent. Ethnicity in Ghana: The Limits of Invention, 2000.

Loxley, John. Ghana: Economic Crisis and the Long Road to Recovery, 1988.

Manoukian, Madeline. Tribes of the Northern Territories of the Gold Coast, 1951.

——. Akan and Ga-Adangme Peoples, 1964.

McCall, D. “Trade and the Role of the Wife in a Modern West African Town.” In Aidan Southall, ed., Social Change in Modern Africa, 1961.

Metcalfe, George. Great Britain and Ghana: Documents of Ghana History, 1964.

Nugent, Paul. “Living in the Past: Urban, Rural, and Ethnic Themes in the 1992 and 1996 Elections in Ghana.” Journal of Modern African Studies 37 (2): 287–319, 1999.

Nukunya, G. A. Tradition and Change among the Anlo Ewe, 1969.

Rattray, Robert S. Ashanti, 1923.

——. Ashanti Law and Constitution, 1929.

Robertson, Claire. Sharing the Same Bowl? A Socioeconomic History of Women and Class in Accra, 1984.

Schildkrout, Enid. People of the Zongo: the Transformation of Ethnic Identities in Ghana, 1978.

Schwimmer, Brian. “Market Structure and Social Organization in a Ghanaian Marketing System.” American Ethnologist 6 (4): 682–702, 1979.

——. “The Organization of Migrant-Farmer Communities in Southern Ghana.” Canadian Journal of African Studies 14 (2): 221–238, 1980.

Vercruijsse, Emile. The Penetration of Capitalism: A West African Case Study, 1984.

Wilks, Ivor. Asante in the Nineteenth Century: The Structure and Evolution of a Political Order, 1975.

——. Forests of Gold: Essays on the Akan and the Kingdom of Assante, 1993.

Web Sites

Aryeetey, Ernest. “A Diagnostic Study of Research and Technology Development in Ghana,” 2000. http://www.oneworld.org/thinktank/rtd/ghana1.htm

—B RIAN S CHWIMMER

Credit : everyculture